Every research journey begins with one big question – main kya find out Karna Chahta hoon? This step is all about identifying and shaping your research problem. You need to figure out what the issue is, why it matters, and how you’ll explore it. Once this is clear, the rest of your research process becomes much smoother. In this section, we’ll cover what a research problem is, why it’s important, and how to define it in a clear, focused way.

Let us understand what is research?

Finding answers to the questions that tickle, haunt, or keep circling your curious mind – simple. Also, if you have the motivation and interest in knowing how and why, then you can be a researcher too.

My mind goes, If we only use 10% of our brain, which 90% should we remove? Funny, right? But then I wonder—who would believe such a silly myth? Or maybe I’m the silly one. So I set out to do my own research to see if it’s true or not. – hope that clarifies something

Let us see what research is in psychology?

Psychology research is about minds and behaviour. Psychologists ask, ‘Why do we feel scared? Why do we dream? Why do friends fight and make up?’ They study people, collect facts, and run experiments to understand how we think and feel.

Example – A curious man named Ebbinghaus wondered, ‘Hmm… why do we remember some things for long but forget others so fast?’ He tested himself with nonsense words, checking memory after hours, days, weeks. The Result: we forget quickly at first, then slower. Spaced practice helps memory last — voilà, the forgetting curve and spacing effect!

The long curves show how memory fades with time and how revision helps. After one day, most is forgotten; by day two only about 20% remains. But each review boosts retention. That’s why some friends nail movie lines—they revisit them often, so the memories stick.

Why do we really need research when life appears to be going smoothly?

Long ago, people thought the Earth was flat and that leeches could cure any illness. Funny, right? But what looks “fine” often hides big surprises. Research plays a significant role in shaping our daily lives, with examples including COVID-19 vaccines, digital payment systems, affordable solar energy, and educational apps like Byju’s and AI chatbots. Research enables us to question, explore, and uncover truths, driving progress and growth through curiosity, problem-solving, and discovery.

How do we do research?

“Let’s discuss something that will give us an edge in the exam. “

- Start with a question or problem – This blog discusses this topic

- Example -“Why do some students remember better than others?”

- Look at what’s already known – Read books, articles, past studies.

- Make a guess (hypothesis) – “Maybe revision timing affects memory.”

- Collect evidence – Surveys, experiments, interviews, or observations.

- Analyse what you found – Use numbers, patterns, or comparisons.

- Share and discuss – Write it, present it, let others check.

- Update & improve – If results surprise you, tweak and explore more

Now that we know what research looks like in simple, everyday terms, let’s zoom in on how psychologists do it.

Start with a question or problem

In research, we refer to this topic as Identifying the problem.

How to choose a Research Problem in Psychology ?

- Look for gaps or puzzles in knowledge

- Read books, journal articles, or observe everyday life.

- Ask: What do we still not know? or What feels confusing or incomplete?

- Notice real-life issues – My fav.

- Think of problems that affect people around you, like exam stress, social media overuse, bullying, or sleep issues.

- Good research often begins with something relatable and meaningful.

- Make the topic specific

- Avoid vague ideas like “social media.”

- Turn it into a researchable question: “Does scrolling Instagram before bed affect teenagers’ sleep quality?”

- Check relevance and value

- Ask: Will this study help others? Will it contribute to psychology or society?

- Ensure feasibility

- Check if you have enough time, resources, and access to participants.

- A great idea is useless if it cannot be studied properly.

- Frame the problem as a clearly

- Example: “Does meditation reduce exam anxiety among college students?”

- Remember: a strong problem sets the direction for your research

- If the question is unclear or too broad, the whole study can become weak.

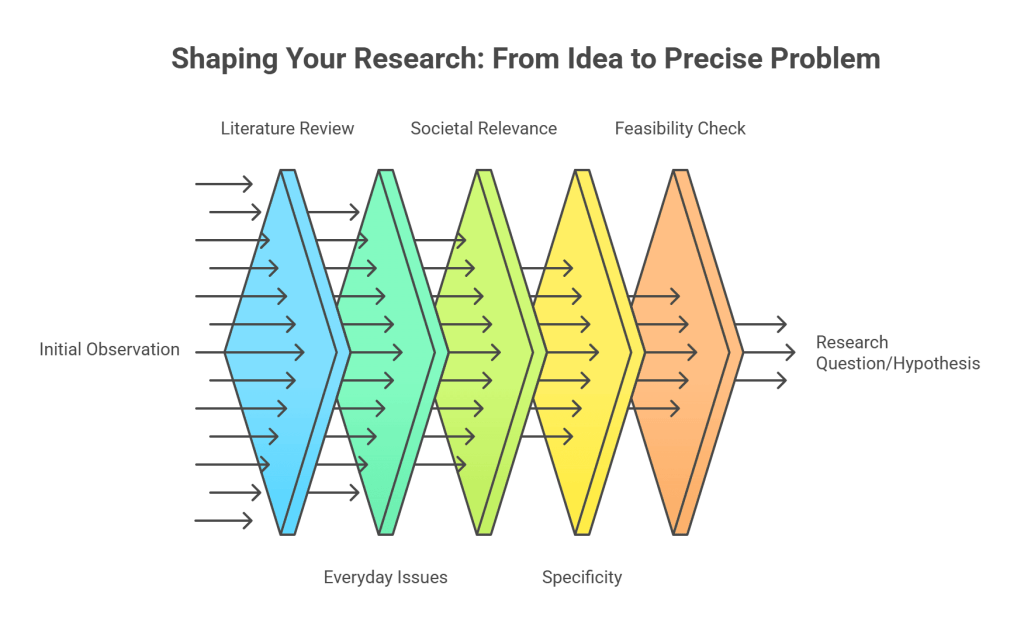

“This illustration shows how scattered initial observations are gradually filtered through literature review, societal relevance, specificity, and feasibility checks, until they emerge as a focused research question or hypothesis.”

Now that you understand what a research problem is, the next step is Figuring out what kind of research you’re actually doing. Don’t worry—researchers before us have already standardised names for different types of research, so everyone can speak the same language and understand each other clearly.

While you were identifying or refining your question, you probably already got a sense of it:

- Will your research join the “research bank”, adding knowledge that others can use later?

- Or is it more applied, aimed at solving a problem—maybe not immediately, but sometime in the future?

- Alternatively, is it urgent, needed right now to tackle an important issue at hand?

This helps you categorise your research correctly : Types of research Based on Purpose.

- Basic (Fundamental) Research: Expands knowledge without immediate practical use aka “research bank material”

- Applied Research: “Solves practical problems” in real-world contexts.

- Action Research: “Solves immediate problems” while improving practice. Common in education, healthcare, or organizational settings. Involves a cyclic process: plan → act → observe → reflect → revise.

Types Based on Time

- Cross-sectional Research

- Observes a phenomenon at one point in time.

- Useful for getting a “snapshot” of the situation.

- Example: Surveying students’ stress levels in September.

- Longitudinal Research

- Observes the same subjects over a long period to track changes or development.

- Example: Following a batch of students from grade 1 to grade 12.

Then Types Based on Approach in Psychology / Social Sciences:

- Experimental Research: Aggressive Approch

- What it is: You actively manipulate one variable to see its effect on another.

- Purpose: To find cause-and-effect relationships.

- Example: Giving one group of students a new study technique and comparing their test scores with a group that didn’t use the new study technique.

- Takeaway: If new study technique caused an effect (increase or decrease in test scores).

- Descriptive Research – Relaxed Approch

- What it is: Observing and recording behaviours, events, or traits in their natural setting to understand qualitative aspects.

- Purpose: To understand what is happening, not why.

- Example: Counting how many students raise their hand during an online class without influencing others.

- Takeaway: Helps Understand natural behaviour, Provides a starting point for future studies,To find trends and patterns

- Exploratory Research – Tedious Approch

- What it is: Used when a topic is new or not well understood.

- Purpose: To gather preliminary insights and identify patterns.

- Example: Asking students how they feel about AI tools in learning, when no prior research exists.

- Takeaway: Opens doors to further, deeper research.

- Correlational Research – Quiet Observing approach

- What it is: Examines relationships between two or more variables.

- Purpose: To see if variables are connected, but doesn’t prove cause-effect.

- Example: Studying whether hours spent on social media relate to stress levels in students.

- Takeaway: Tells us if things move together have relationships but dont affect each other in full capacity. Like if two things, using social media and feeling stressed, go up or down together, but doesn’t say which one makes the other one go up or down.

You might be wondering, “Why are there so many types of research if research is just one thing?” Good question! The truth is, research looks different depending on why you’re doing it, how you’re doing it, and how long you’re studying it for. That’s why researchers before us made categories—so we can all explain our work clearly and in the same language.

Imagine you’re in your Master’s, and a professor asks: “What kind of research are you doing?” If you only reply, “Oh, I’m doing research on psychology experiments,” it won’t be enough. They’ll immediately ask you: “Okay, but what kind of research exactly?”

Here’s how you can now explain:

- You might say: “I’m doing a Correlational Research (Approach) because I want to see the relationship between two variables, like social media use and stress.”

- Then you can add: “It’s a Cross-sectional Research (Time) because I’m collecting data only once, not following people for years.”

- Finally, you can say: “It’s also a Fundamental Research (Purpose), because I’m adding knowledge to the research bank—it won’t solve a problem today, but someone else might use my data later.”

CUET-type Questions

1. A researcher wants to understand why students forget most of what they study in just a few days. He sets up experiments on himself, testing memory of nonsense words over time. Which type of research best fits this?

- Applied Research

- Fundamental Research

- Action Research

- Exploratory Research

2. If a psychologist is interested in studying how many students raise their hands in an online class, without changing their behaviour, this is:

- Correlational Research

- Descriptive Research

- Experimental Research

- Action Research

3. A researcher studies whether Instagram use before bed is related to teenagers’ sleep quality but does not prove cause-effect. This is:

- Correlational Research

- Experimental Research

- Exploratory Research

- Applied Research

4. Which of the following is an example of Cross-sectional research?

- Tracking a child’s personality from age 5 to 18

- Comparing stress levels of college students in September through a one-time survey

- Testing whether meditation reduces exam stress

- Reviewing studies to check if social media causes depression

5. “Research that adds to the ‘knowledge bank’ without immediate practical application” refers to:

- Applied Research

- Action Research

- Fundamental Research

- Descriptive Research

6. In Longitudinal Research, data is collected:

- At a single point in time

- Repeatedly over a long period of time

- Only from one participant

- In a laboratory setting

7. Which type of research involves the cycle of plan → act → observe → reflect → revise, and is common in education and healthcare?

- Action Research

- Applied Research

- Exploratory Research

- Experimental Research

8. A psychologist tests whether a new study technique improves exam scores by giving it to one group and not to another. Which type of research approach is this?

- Experimental

- Descriptive

- Correlational

- Exploratory

9. Which of the following is an Exploratory Research example?

- Testing if yoga reduces stress before exams

- Asking students about their views on AI in learning, when little prior research exists

- Measuring whether students who sleep less score lower on tests

- Observing how many people yawn in a classroom

10. A Master’s student tells his professor:

“I’m doing Correlational Research (Approach), Cross-sectional (Time), and Fundamental (Purpose).”

What does this mean?

- He is studying cause-effect of variables across time.

- He is studying relationships at one point in time, mainly to add knowledge.

- He is solving an immediate problem in real-world settings.

- He is manipulating variables to improve practice.

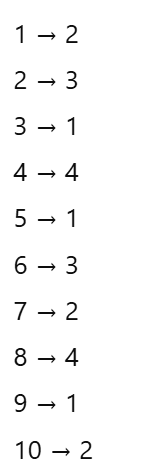

Answers Mapping:

Leave a Reply